Bahasa Indonesia: klik di sini

On April 19, 1942, in Gowa, just outside Makassar, the leader of the Chinese-Indonesian community on Celebes, Major Thoeng Liong Hoei (湯龍飛, in Mandarin: Tang Longfei) and four of his sons and two sons-in-law, were beheaded by the Japanese. The reason for this is their opposition to the Japanese occupation of South Sulawesi and the refusal to collaborate. Many others in the Sino-Indonesian community in Makassar were also arrested and killed. Major Thoeng is now a resistance hero not only in Indonesia, but also in China, because he took on the Japanese as an overseas leader. In the Netherlands he disappeared from memory after the Second World War. His name appears only once in a tiny newspaper article, on October 10, 1948, in which it is reported that the Japanese Vice Admiral Mori had ordered the execution.

Before the war things were different.

Major Thoeng was born in 1872 in Makassar, South Celebes (now: Sulawesi). His father, Thoeng Tjam (1845-1910, 湯河清 or Tang Heqing) is an immigrant from the Chinese province of Fujian, where the majority of the Chinese-Indonesian population originates. Thoeng Tjam makes the classic paperboy-to-millionaire career in Makassar. At the age of 13, he starts out as a tobacco peddler and then works in a fishmonger’s shop, which he takes over. At the end of his life he is a multimillionaire, owner of a large company, with ships and possessions in Surabaya, Celebes and Singapore.

His success is not lost on the Chinese-Indonesian community, and in 1893 he is appointed Captain of the Chinese. In the Dutch colonial system, this is not a military position, but a leadership title. The Captain is expected to lead the Chinese community, and to ensure order and tranquility. There is a role in the administration of justice, civil status and payment of taxes to the colonial government. Thoeng Tjam died in 1910 after a short illness at the age of 65.

His son, Thoeng Liong Hoei, followed in his father’s footsteps. He also becomes Captain of the Chinese, inheriting his fortune but also his generosity to charities. In 1916, for example, he donated a thousand guilders to the victims of the Zuiderzee flood that ravaged The Netherlands in January of that year. In 1923, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Queen Wilhelmina’s government, he also donated valuable furniture. The furniture is made of dark brown rosewood – with a red glow – with surfaces of fine blue and green veined marble and inlaid mother-of-pearl details. It consists of eight armchairs, twelve smaller seats, five couches, including one huge, two large tables and eight side tables. Coincidence or not, a short time later he was appointed Knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion. In 1926 he was promoted to Major of the Chinese, a title reserved for the leaders of the largest cities in the Dutch East Indies, such as Batavia and Surabaya.

He also donates large sums to China, for example to help internal refugees. Meanwhile, the business empire is growing steadily. The assets include a large real estate portfolio in Makassar including the luxurious Empress hotel and most commercial areas north of Makassar. He also owns large copra plantations for the production of coconut fat in Selayar, an elongated island south of Makassar. At that time, the Dutch East Indies produced 30-40% of the world trade in copra. In his house, located at Boekekang 1 (now Jl. Bacan 5), large parties are organized, for example to make an inspector’s stay as pleasant as possible (Soerabaijasch Handelsblad, 27-3-1933).

In 1942 everything changes.

After the declaration of war by the Netherlands on Japan in December 1941, the Japanese air force starts attacking Makassar in January 1942. The Chinese quarter is also heavily bombed. On the night of February 8-9, the Japanese troops land and enter the city. Residents of the Chinese quarter, some say thousands, hide or flee to the countryside, where they are taken care of by the local population. Major Thoeng and his family also fled the city. However, he is arrested and imprisoned just outside Makassar along with four of his sons and two sons-in-law. According to the family in Indonesia, the Japanese tried to win him over with money and threats, but he refused to collaborate. Finally, they killed him along with his sons and sons-in-law, on orders, so we know, from Vice Admiral Mori. They were buried on the spot in an unmarked grave near the village of Sungguminasa in Gowa.

The Major’s three wives are able to escape to the countryside, and four sons and a daughter also escape the Japanese. According to the family in Makassar, they had been hiding during the war somewhere in the countryside in such places as in Camba near Maros and Pangkep or Malino. It was customary for wealthy Chinese to have two or three wives. Two of them came from China and Singapore. The third was Indonesian, who according to family history was a descendant of the princes of Gowa and the Javanese prince Diponegoro. In total, the Major had 10 children, eight sons and two daughters. Two of his grandsons still live in the ancestral home on Jl. Bacan, which also houses an impressive painting of the Major, dressed in uniform and decorated with medals from the Netherlands, China and Taiwan.

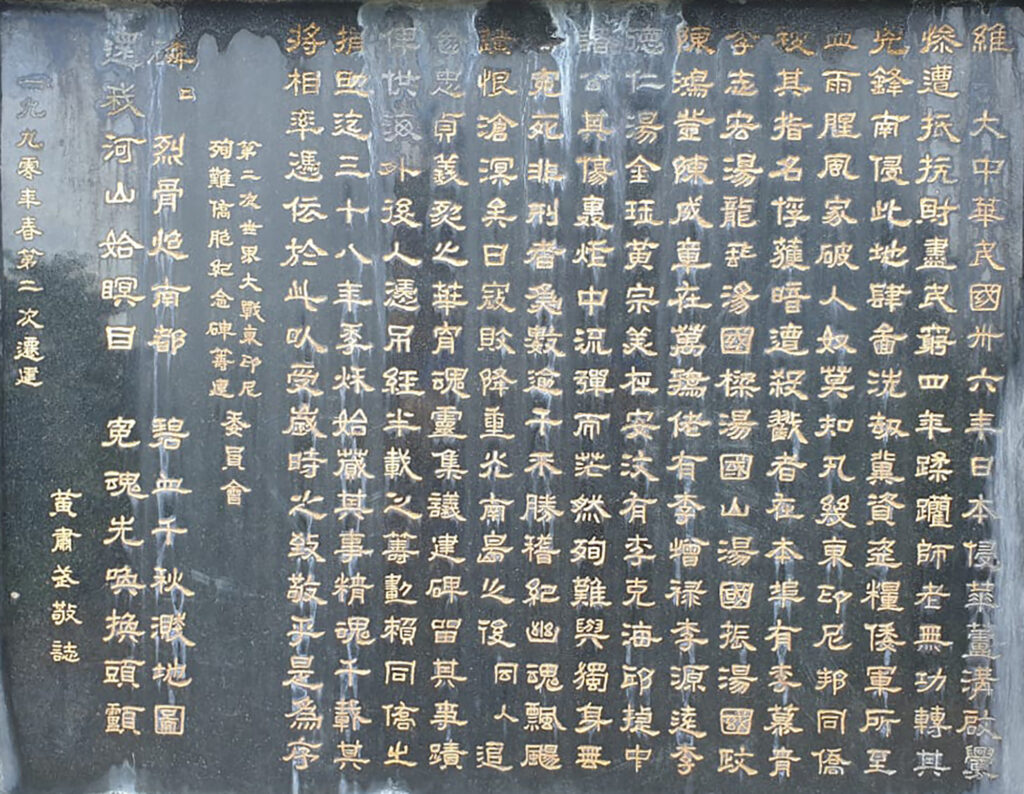

After the capitulation of Japan in 1945, the family traced the grave of the Major and his sons (-in-law) in Gowa and reburied the remains at Jl. Irian. The graves have since been moved twice due to the continuous expansion of the city. After some research it appears that the grave can still be admired in the Chinese cemetery Bolangi, half an hour outside Makassar. The memorial stone that was erected in Makassar in 1949/1967 as a tribute to the Chinese-Indonesian victims of the Japanese occupation in Sulawesi and the Moluccas has also been placed there (Photo 4). The text speaks of bombings and thousands of deaths in the Chinese community. Seventeen are mentioned by name, including the Major and his family.

In addition to Indonesia, Major Thoeng is also seen as a resistance hero in China. A Chinese leader abroad who took on the Japanese, who paid the ultimate price for his resistance. This most clearly takes shape in his ancestral village of Xinchun (鄉新春村) in Fujian Province. His father, Thoeng Tjam, gained an important position in the village after his food aid during the famine of 1880 and built an ancestral house there.

And in the Netherlands?

Sam Tjioe (Amsterdam, 1952), grandson of Thoeng Soat Kie, one of the Majoor’s daughters, remembers that after the war his father and other relatives tried to continue business but saw the family capital evaporate due to expropriations and the devaluation of the rupiah. The Major is remembered in the family for his loyalty to the Netherlands and the Queen. The story goes that – even under threat of death – he refused to swear allegiance to the Japanese Emperor because of his oath of allegiance to Queen Wilhelmina. In the end, neither the Netherlands nor the royal family showed much interest in the loyalty of the Chinese Indonesian leader. Major Thoeng seems to have disappeared from Dutch history. Perhaps the precious furniture is still present somewhere in a palace, or the wedding gift that the Major presented to Princess Juliana and Prince Bernhard in 1936. A jewelery box made from the shells of turtles, with a map of Celebes on the top in platinum and gold. But that’s all. Wouldn’t it therefore be time to give Thoeng Lioeng Hoei, and with him the many Chinese-Indonesian victims of the Japanese occupation, the recognition they deserve in the Netherlands?

This is an English translation of the author’s version of an article originally appeared in Dutch in Indies Tijdschrift 2021 #2, p16-17.

Acknowledgements

I thank Adil Nurimba and Freddy Thoeger for research in Indonesia, Hauw Ming, Zhang Din and Huihan Lie (My China Roots) for Chinese translations, Sam Tjioe for information from the Netherlands, and Frans and Johan Helling for connections and assistance in researching this history.

Sources

- Oral history from the Netherlands and Makassar

- WWII Memorial Chinese Victims, Bolangi, Indonesia

- Epitaph Thoeng Lioeng Hoei, Bolangi, Indonesia

- Sin Po, Special Issue, 10-10-1946

- Yerry Wirawan. Sejarah Masyarakat Tionghoa Makassar. Jakarta, 2013.

Appendix

WWII memorial full translation. The translation is kindly provided by My China Roots (mychinaroots.com).

Stele:

Japan invaded China in 1937[1]. After they initiated the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, they faced opposition, resulting in the drain of finance and the destitution of the people. They ravaged for four years without success. Then, they switched targets and invaded the south, engaging in unbridled robbery and stealing food. Bloodshed followed wherever the troops went. Thousands of families were destroyed, and many people were enslaved. We list here the names of the overseas Chinese who were captured and assassinated in Negara Indonesia Timor.

The people who were killed in Makassar include: Li Muqing / 李慕青, Li Zhihong / 李志宏, Tang Longfei / 汤龙飞, Tang Guoliang / 汤国梁, Tang guoshan / 汤国山, Tang Guozhen / 汤国振, Tang Guozheng / 汤国政, Chen Hongdeng / 陈鸿登, Chen Xianzhang / 陈咸章;

In Manado, those killed include Li Zenglu / 李增禄, Li Yuanyuan / 李源远, Li Deren / 李德仁, Tang Jinjue / 汤金珏, and Huang Zongying / 黄宗英;

In Ambon, those killed include Li Kehai / 李克海 and Qiu Jiezhong / 邱捷中, among others.

Thousands of people were killed without our knowledge, either by a stray bullet, or by wrongful accusation and torture in prisons where they ultimately died alone. The Chinese believe that the ghosts of these unfortunate victims wander the earth with grudges in their hearts. After the Japanese army surrendered and we recovered lost territory, we suggested we raise funds to build a stele in memory of our Chinese loyal martyrs. It would record their story for future generations to learn. Our overseas Chinese donors helped make this possible after a half-year of planning. In October 1949, we uncovered the stories behind those ghosts and engraved them onto this stele as a mark of respect. Here is the preface.

Preparations for the construction of a cenotaph for overseas Chinese who died in World War II while serving on the Negara Indonesia Timor committee

Poem:

The flames of the dead are bright enough to illuminate the land, and the blood of the innocents has bled across it. My hatred will not fade until the land is reclaimed. Only then will the souls of millions be able to rest in peace.

Huang Suwu wrote this respectfully.

[1] The original text is 1947 but the correct date should be 1937.